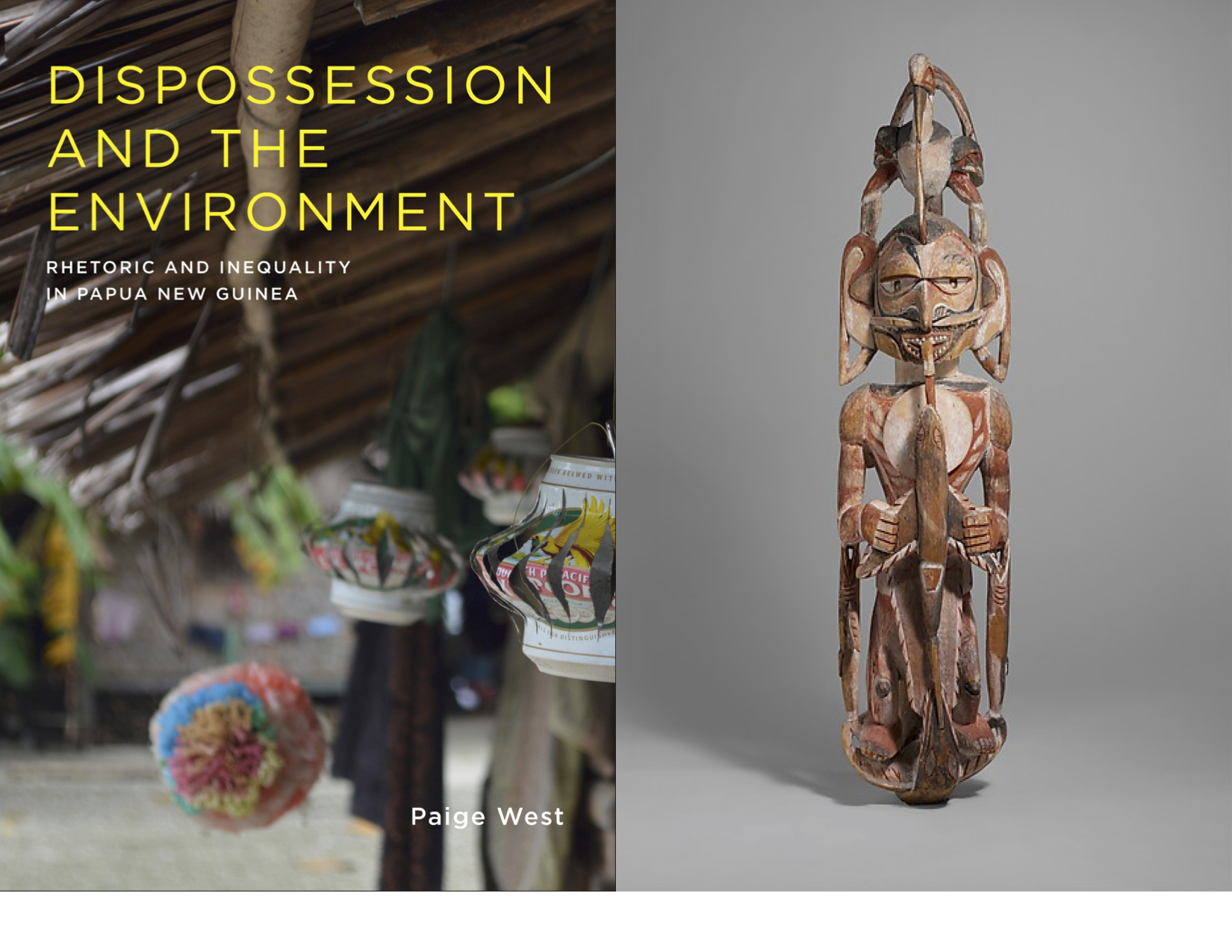

This is the first in a series of interviews TRIP will feature with grantees to bring attention to issues and remarkable innovators in global culture. TRIP spearheaded the development of The Colleen Ritzau Leth ’08 Family Fund for International Research to provide ongoing support to Barnard College faculty conducting research that promotes mutual understanding between diverse societies and allows Barnard’s exceptional faculty to engage deeply in original studies on topics spanning international relations, peace building studies, economics, and human rights. The inaugural grant was awarded to Professor of Anthropology Dr. Paige West, who recently published Dispossession and the Environment (Columbia University Press, 2016), a study on the impact of NGOs, tourism, and foreign visitors on Papua New Guinea. Dr. West is currently working to preserve the island’s threatened cultural tradition of Malagan—intricate, layered carvings that communicate ancient histories and local knowledge through their motifs.

This is the first in a series of interviews TRIP will feature with grantees to bring attention to issues and remarkable innovators in global culture. TRIP spearheaded the development of The Colleen Ritzau Leth ’08 Family Fund for International Research to provide ongoing support to Barnard College faculty conducting research that promotes mutual understanding between diverse societies and allows Barnard’s exceptional faculty to engage deeply in original studies on topics spanning international relations, peace building studies, economics, and human rights. The inaugural grant was awarded to Professor of Anthropology Dr. Paige West, who recently published Dispossession and the Environment (Columbia University Press, 2016), a study on the impact of NGOs, tourism, and foreign visitors on Papua New Guinea. Dr. West is currently working to preserve the island’s threatened cultural tradition of Malagan—intricate, layered carvings that communicate ancient histories and local knowledge through their motifs.

Q. How did you become interested in Papua New Guinea?

I became an anthropologist because of Papua New Guinea. When I was a child, like so many of us, I read National Geographic. So the sense of other people and others places was in my consciousness from an early age, and I was interested in Papua New Guinea. As happens, I forgot about it. [But] during my senior year of college, I read a book by Roy A. Rappaport (d. 1997), [the anthropologist who wrote about the relationship between the island’s culture and economy]. I realized in that class that I was incredibly passionate about the environment and culture—the island is both the most biologically and the most culturally diverse place on Earth.

Q. You are now an authority on Papua New Guinea and respected locally. In fact, you were recently approached by Papua New Guineans themselves. What did they share with you?

My research partner and I were approached by elders from the New Ireland communities. New Ireland is one of the large islands to the north of New Guinea. They were concerned about Malagan carvings—the lynchpin of local ceremonies and culture. These elders explained that there are only six master carvers alive today and these men are in their late 50s and early 60s. When they die, the knowledge of both Malagan carving and the underlying ontology and epistemology of the Malagan ceremonies will be lost.

Q. What makes the objects important and unique?

Malagan carvings are represented in public collections all over the world, like The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History. These are the most collected, most spectacular objects from the island. They have this incredible power because their motifs contain family histories, origins, and crucial knowledge about the relationships between people, plants, animals, and spirits. The carvings themselves are not objects of value for Malagan culturally; rather, it is the imagery, or the motifs, that are carved onto the objects, that contain what is of value. Only master carvers can produce these carvings and there are strict rules for when, where, and to whom a carver can pass on his craft and knowledge.

Q. How are you using the funds?

Prior to this gift, we received a U.S. Ambassador’s Fund For Cultural Preservation Grant to begin working with the last living master carvers to document their knowledge. This support is unspecified and unrestricted, which is allowing us to really move forward with this project, expand our team of collaborators, and do environmental and cultural conservation together. It is allowing us to buy tools; make introductions for carvers; and connect with researchers at institutions like The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Australian Museum. The support from The Colleen Ritzau Leth ’08 Family Fund is also supporting our long-term goal, which is to help Papua New Guineans who want to conserve and revitalize their tradition access the people who can help them do it. We want to get these carvers hooked into global networks of art and conservation that value these objects and help the carvers articulate to younger people in their societies why Malagan matters.

Q. You mentioned that the funds have allowed you to do environmental and cultural conservation together. How so and what is the urgency?

We believe that this kind of work can really help articulate the connection between art and the natural world, and we want to help local people understand why it so important that these traditions be talked about, discussed, and argued over right now. There is this really fundamental connection through these objects between the culture and the environment in Papua New Guinea. The environment is changing very quickly: sea levels are rising rapidly and there is extensive bleaching of coral atolls. The Malagan carvings have five different layers of stories in them and all of these stories have an ecological and cultural and ecological component. The ecology motifs are very site specific to where the carvers are from. Most of these villages will have to move [as a result of rising sea levels], and the ecological basis for their societies will be gone. These carvings house the memory of that.

Q. The Colleen Ritzau Leth ’08 Family Fund for International Research is a permanent endowed fund that allows a diverse cross section of Barnard’s exceptional New York City faculty to engage deeply in research. As the inaugural recipient, why are funds like this important?

It is very important because it will help myself and other faculty to develop new kinds of research projects and programs that might not traditionally fit within the funding structure of our disciplines. This fund will help the faculty at Barnard break down interdisciplinary boundaries when we are asking new kinds of questions.

Q. In closing, your recent book is a searing study of how local knowledge is devalued and eroded by journalists, developers, surf tourists, and conservation NGOs in Papua New Guinea. What is the connection between dispossession and the threatened knowledge of the Malagan carving tradition?

Europeans, Americans, and Australians have built academic careers, museum collections, and scientific bodies of knowledge that really started in Papua New Guinea. There is this way in which the people and the places from which this knowledge was extracted have never benefited directly from that knowledge, nor have they ever had the opportunity to work in the fields developed through that knowledge. When I think about dispossession, in addition to extraction of natural resources, for example, I think about this more ephemeral thing—knowledge.

#culturematters

Image: Funerary Carving (Malagan), Late 19th-early 20th century. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum